Reports

Advocates of Silenced Turkey’s reports are investigative deep dives into the erosion of human rights and civil liberties in Turkey. These reports examine patterns of repression against educators and students, the dismantling of civil society groups, misuse of anti-terror legislation, and the targeting of activists and ordinary citizens both at home and abroad. They also document systematic torture, judicial failings, gender-based abuses, and the plight of refugees fleeing persecution. Together, these analyses shed light on the mechanisms of authoritarianism and call for international accountability and solidarity.

Academic Voices Silenced in Turkey

6,081 academics dismissed in Turkiye—freedom is the first casualty when universities become battlegrounds for power....

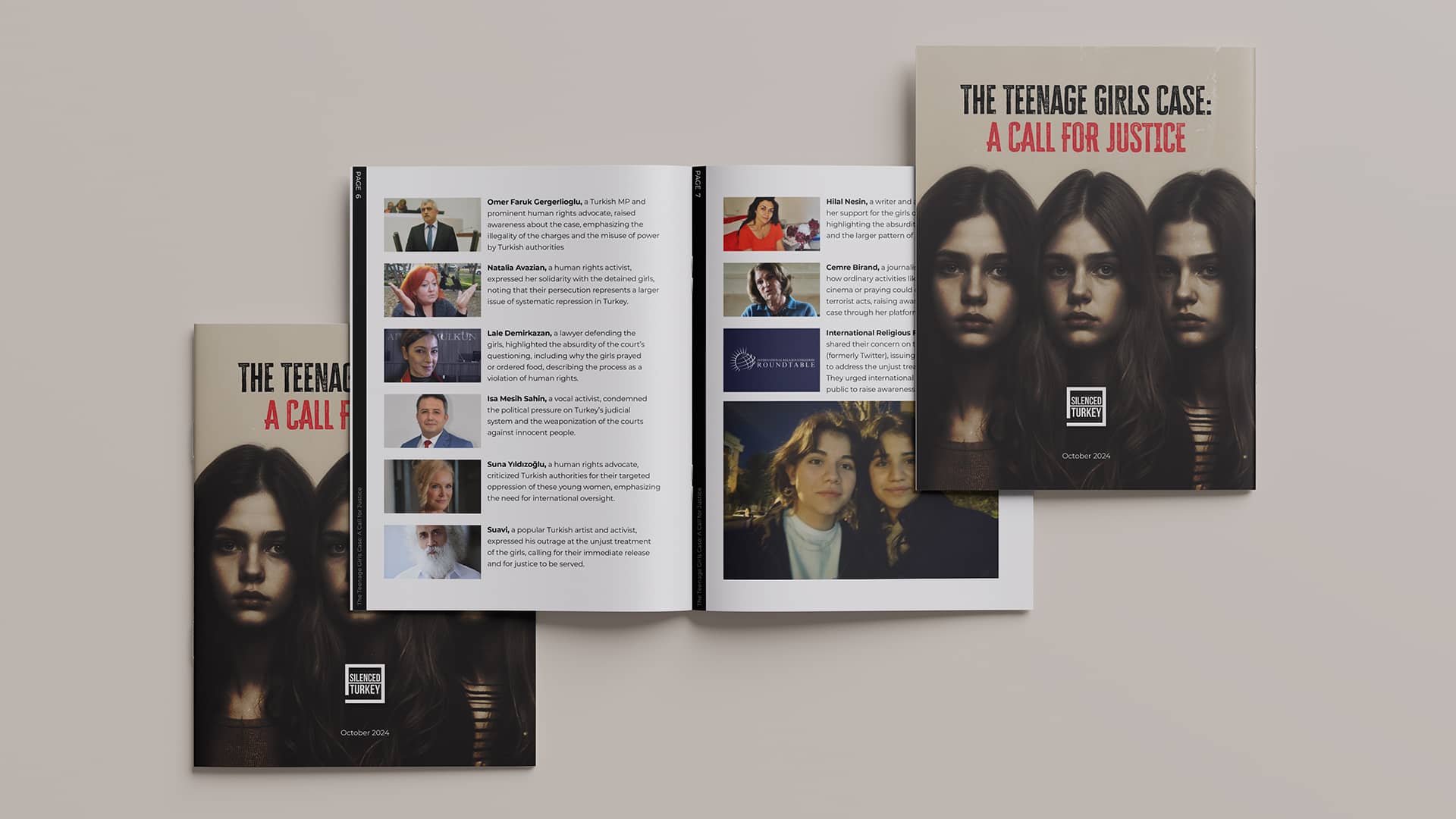

Read MoreThe Teenage Girls Case: A Call for Justice

In May 2024, a large-scale anti-terrorism operation took place in Istanbul, where 48 individuals, including high school ...

Read MoreThe Death of Fethullah Gülen: A Discourse Analysis in Turkish and International Media

On October 20, 2024, Fethullah Gülen, the founder of the Hizmet Movement/Fethullah Gülen Community, passed away in the U...

Read MoreThe Crackdown on Humanitarian Aid in Turkey

This report, issued by the Advocates of Silence Turkey (AST), details an alarming misuse of counterterrorism laws in Tur...

Read MoreSpecial Report: “Authoritarianism Unveiled: Turkey’s Human Rights Catastrophe”

This special report highlights the concerns raised by Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe, Dunja Mija...

Read MoreBeyond Turkey’s Borders: Unveiling Global Purge, Transnational Repression, Abductions

Turkey’s pursuit of alignment with the principles of the European Union has been marred by the government’s increasingly...

Read More143 SOCIAL GENOCIDE PRACTICES IN ERDOGAN’S TURKEY

This work presents an exhaustive list of flagrant human rights violations to the degree of social genocide, perpetrated ...

Read MoreTorturers Report 2 – Torture and Human Rights Violations in Turkey

Advocates of Silenced Turkey (AST) prepares reports to record and document crimes against human dignity, such as torture...

Read MoreTurkey’s Human Rights Record In Numbers

Turkey, which was once touted as a model country, has now become a case study of what can happen to a country that moves...

Read More“Global Purge” : 144 Abductions Conducted by the Turkish Goverment in Turkey and Abroad

Since July 2016, the Turkish government went on to imprison hundreds of thousands of homemakers, mothers, children, babi...

Read MoreErdogan’s Torture Squads and Torture in Turkey as a Grave Human Rights Violation

THE CRIME OF TORTURE As a member of the Council of Europe, Turkey has ratified the European Convention on H...

Read MoreWomen’s Rights Violations by the Turkish Legal System

This report is based on a combination of desk research and interviews held by Advocates of Silenced Turkey. For the inte...

Read MoreTurkey’s New Normal: Torture and Ill-Treatment

This pamphlet prepared by the Advocates of Silenced Turkey's Right to Life Committee provides an overview of official re...

Read MoreEuropean Court of Human Rights Should Reconsider Judicial Independence in Turkey Before Referring Cases to Domestic Authorities

This position paper critically examines the European Court of Human Rights' (ECtHR) approach to cases originating from T...

Read MoreComparative Analysis of Different Countries’ Approaches Towards Turkish Asylum Seekers Linked to the Gulen Movement

Turkish government has been targeting dissidents from various ideologies recently. One of these opposition groups, the G...

Read MoreRefugees and Latest Pushbacks in Greece

Thousands of refugees fleeing their homeland due to violence, terror, or political prosecution use Greece as an entry ga...

Read MoreErdogan’s Tool to Take Over Hizmet Schools Illegally: The Maarif Foundation

The report talks mainly about the recent activities of the Turkish government putting education at risk through illegal ...

Read MoreA Predatory Approach to Individual Rights: Erdogan Government’s Unlawful Seizures of Private Properties and Companies in Turkey

Property rights in Turkey are no longer protected because of the disregard the Erdogan government has shown to the right...

Read MoreAMERICANS ARRESTED IN TURKEY: ANDREW BRUNSON AND OTHERS

The Evangelical Pastor Andrew Craig Brunson, an American citizen, was taken into custody in October 2016 in Izmir, Turke...

Read MoreI Cannot Say We Are Absolutely Safe Even Abroad

This report examines the extraterritorial threats faced by supporters of the Gulen Movement, also known as the Hizmet Mo...

Read MoreErdogan’s Long Arms: Abductions in Turkey and Abroad

Turkey’s struggle to draw the country more in line with the pillars of the European Union faced a long and accelerating ...

Read More