Book Publications

WHAT IS APH PROJECT?

APH (Archiving Persecution of Hizmet Movement) is a comprehensive documentation project aimed at recording the human rights violations and persecution faced by members of the Hizmet Movement, especially after the failed coup attempt on July 15, 2016. The goal of APH is to preserve testimonies, raise awareness, and ensure future generations do not forget these injustices.

What does the APH project include?

- Audio recordings: Over 1,200 hours of interviews and testimonies across 280+ audio files

- Written documents: More than 100 written stories, letters, diaries, and personal reflections

- Books: 32 published books and additional art-based projects such as graphic novels and sketch works

- Poetry and short story collections: Many poems and stories shared as audio narrations and videos on YouTube.

- Success stories: Inspiring stories of resilience and achievement despite ongoing persecution

APH is not just an archive—it is a project of memory, testimony, and resistance. Let me know if you’d like a more concise or design-friendly version for a flyer or presentation.

Justice Delayed is Justice Denied

This book is based on long-term observations, social events and what is being done to address human rights violations. I...

Escape from Turkey – Bilingual (English-Turkish)

These are the true stories of two individuals—one a former lawyer, the other a distinguished scientist. You will witness...

Stories of Hope 1 – Bilingual

This bilingual book features heartfelt stories written by refugee and oppressed children between the ages of 10 and 18. ...

Echoes of Justice: 100 Kahoot Questions on Human Rights

The Kahoot competitions we organize every month to raise awareness among young people about human rights violations worl...

The Life and Legacy of Gokhan Acikkollu: A Teacher Tortured to Death

This book shares the story of Gökhan Açıkkollu, a dedicated teacher who was tortured to death in police custody after th...

Stories of Hope 1

"The Stories of Hope: Written by Children - Refugee and Oppressed" is a compiled selection of the stories submitted for ...

Broken Lives: Stories from New Turkey

When they couldn’t find the old man at his home, they did something which was probably not seen in the history of law be...

Silent Scream: True Stories of Oppression in Turkey

The three true stories in this book are about the three of the countless brave women in Turkey who fought against ex...

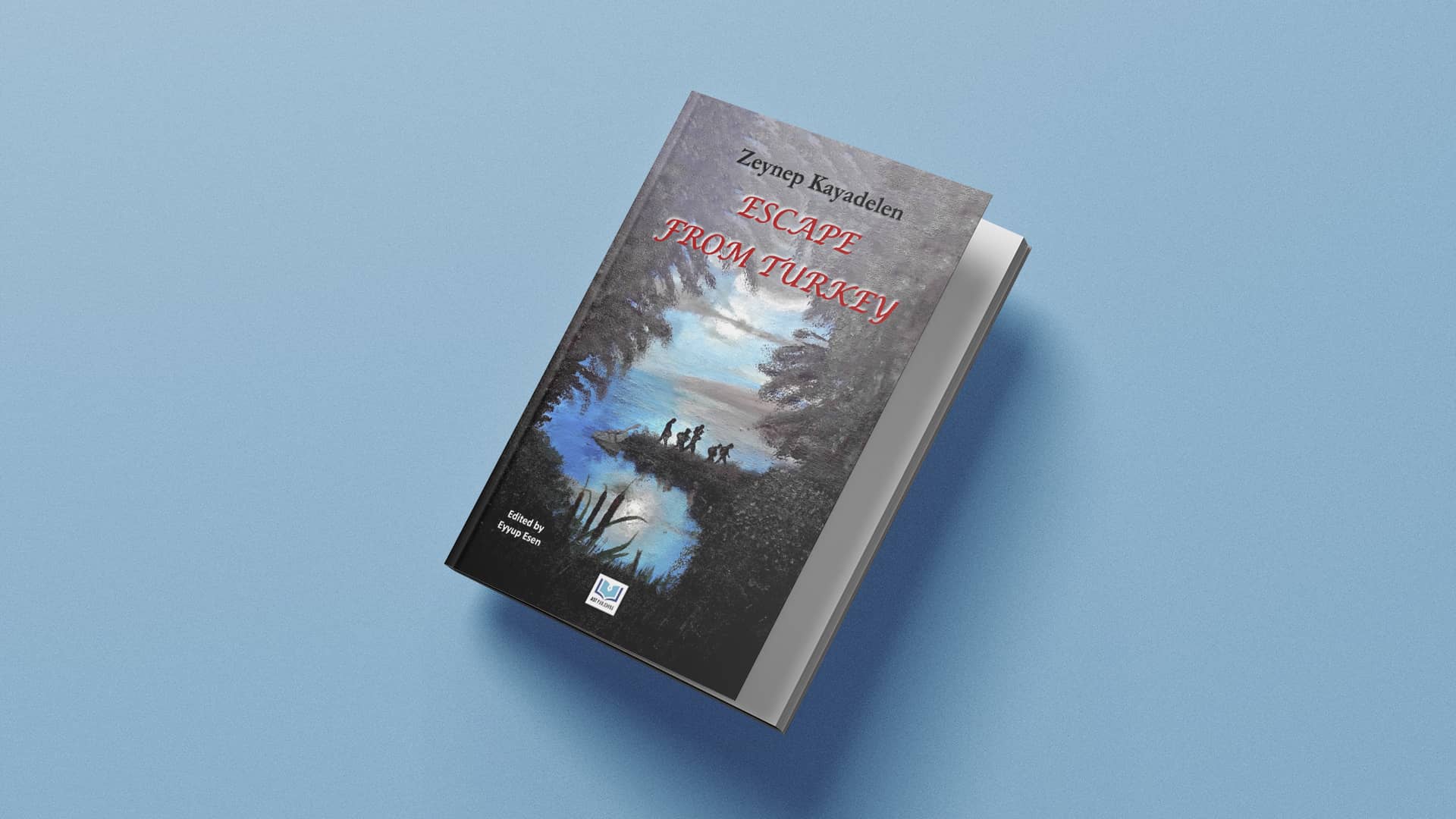

Escape from Turkey

These are the true stories of two individuals—one a former lawyer, the other a distinguished scientist. You will witness...

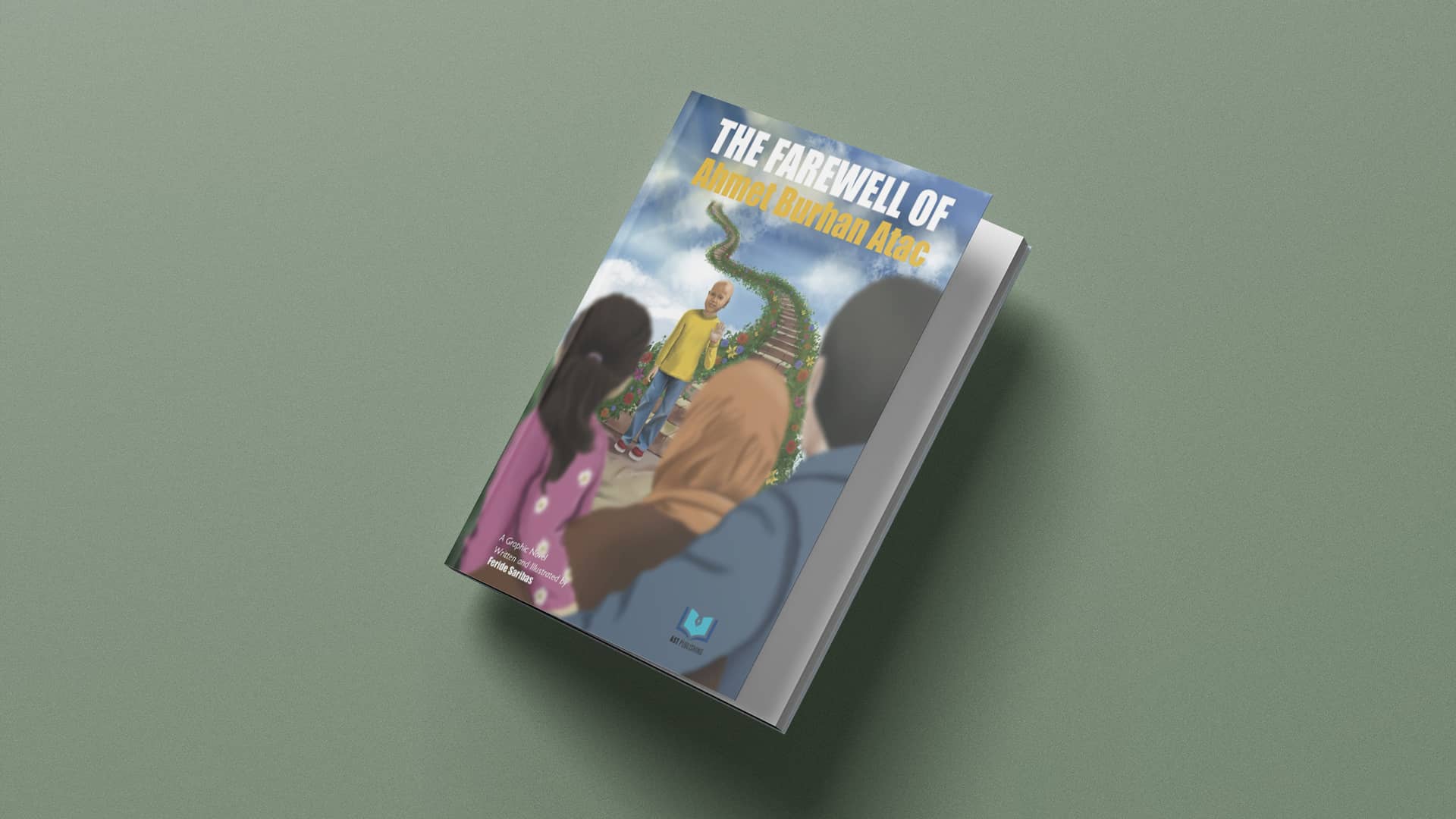

The Farewell of Ahmet Burhan Atac

This graphic novel outlines the end of Ahmet Burhan's short life of 8 years, in particular the time period from July 15t...

A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words The Illustrations of a Teacher in Prison

Yolgezer, a formerly imprisoned artist, invites the world to see the dire human rights violations in Turkey....

The Baby in the Bag

The title refers to the book's flagship story of the same name, an intense story of a mother's requirement to hide her n...